A heat recovery ventilator (HRV), sometimes called an air-to-air heat exchanger, is different than conventional vents and fans. With standard ventilation, air circulates through static, open vents or is expelled by fans, such as those used in bathrooms, kitchens, and attics. When room air escapes or is expelled, the energy that was used to heat or cool it is wasted.

How can you ventilate a house without letting costly heated or cooled air out the window? Meet the heat recovery ventilator.

An HRV can save 75 percent or more of that wasted energy. As it pushes out stale air, it pulls in fresh air, and—with little or no mixing of the two air streams—it transfers the heat or chill from the outgoing air to the incoming supply. The fresh air arrives preheated or precooled and, with some units, prehumidified or dehumidified.

Some HRVs mount like a room air conditioner in a window or wall opening. These are meant to handle individual rooms that have ventilation problems such as bathrooms, laundry rooms, artist’s studios, and darkrooms.

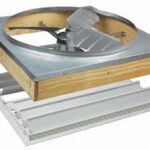

Larger, whole-house HRVs provide fresh air to all rooms. They often require routing ductwork to several places—to rooms where you want to exhaust stale air, particularly bathrooms, laundry rooms, and kitchens; to the outdoors; and often to the central heating and air-conditioning system’s return-air supply.

Though whole-house systems are installed primarily in new houses, they can be retrofitted into some houses that have good access for ductwork, particularly those with unfinished basements. If there is already existing ductwork, installation of some systems is greatly simplified because it can take advantage of the existing return-air system.

The cost of a ducted, whole-house HRV depends on the specific model, the amount of ductwork and accessory material needed, and the difficulty of installation. The units alone range from a low of $400 to about $1,500, with most running from $500 to $900. The only way to estimate the total cost with installation is to get bids from air-conditioning contractors.

Mounted, room-sized models run from $350 to $450. Find out from your utility company if they offer rebates for installing HRVs. The amount of energy needed to run an HRV varies widely from one model to another and depends on the capacity of the unit.

A variety of sizes are available. Carrier, for example, makes 18 different models ranging in capacity from 150 to 1,270 cubic feet per minute (CFM). The right size to buy depends on the number of occupants and the cubic capacity of the rooms or house you wish to ventilate.

For complete ventilation, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) recommends replacing indoor air with at least 15 CFM per occupant. Sizes and lengths of ductwork runs can affect efficiency, so it’s important to work with a contractor when planning a system.

Is a Heat Recovery Ventilator Right for You?

An HRV is an effective way to ventilate a very “tight” (well-insulated) house experiencing high energy prices. A tight house collects more humidity and pollution than one with a lot of air infiltration. If a house has excess infiltration through leaky windows and a poorly insulated shell, air flow bypasses the heat exchanger, negating its work.

Though they are considered to be most effective in very cold climates, HRVs make sense where summers are hot, too. The actual economics indicate that HRVs may offer better energy savings in hot, air-conditioning climates.

Electricity needed for air conditioning is much more expensive than any other fuel, so every BTU you can recapture may have three times the value of the savings of heating fuels like natural gas. (A BTU measures the quantity of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 pound of water 1 degree F.) Of course, the higher the cost of energy, the more an HRV makes sense.

HRVs are practical for houses that have very high winter humidity, and enthalpy-type HRVs can assist air conditioning in climates where summer humidity is high. An HRV may also be a practical solution where there is a radon or formaldehyde pollution problem, though this should be determined by a qualified air-quality expert.

In mild climates, exhaust-only ventilation may be a better solution than an HRV. Where outdoor winter temperatures are fairly high, there isn’t sufficient recoverable heat to repay the investment. And for cooling, the difference in temperature between indoor and outdoor air often isn’t high enough to justify the cost of installation, operation, and maintenance.

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has:

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has: