Save money on utility bills by illuminating your home and warming its interior spaces with natural daylight.

“Daylighting” is the act of lighting interior spaces by natural means. Any time you’re able to light a room with a window or skylight instead of flipping on a light switch, you are daylighting. It’s that simple.

On the other hand, most designers note that daylighting also involves control. According to the ENSAR Group, a Boulder, CO.–based architectural and consulting firm that specializes in daylighting, “We see daylighting as the art of bringing natural light into a space in the best way for that space…understanding what light does and how to manipulate it to meet the needs of the people in that space.”

Daylighting solutions can be quite simple or very complex, depending upon the structure and the situation. A comprehensive approach, particularly in commercial and institutional building design, must consider many factors: the climate, the sources of natural light, the necessary measures for controlling light, heat gain, and heat loss, the occupancy and use of the building, and so forth.

Such solutions often involve special glazing, coatings, or films; shading and light-reflecting and -diffusing surfaces; special controls that reduce artificial light when it isn’t needed; and more.

Very sophisticated systems may even include sun-tracking mirrors and lenses, light pipes, and fiber-optic cables, but these types of comprehensive daylighting elements are not common in houses. “Daylighting isn’t really a term that’s normally applied to a house,” according to the Passive Solar Council. “You can daylight a library or a school, but for a home true daylighting is pretty unusual.”

Natural Light & Daylighting Techniques

Since the oil crunch of the 1970s, architects, engineers, and homeowners have sought new ways to reduce America’s reliance on traditional energy sources for heating and lighting homes. Certainly one of the most popular and promising answers to emerge has been solar energy. “Although nobody has officially counted, we project there are well over half a million passive solar houses in the United States,” says a spokesperson for the Passive Solar Industries Council.

There are experts who specialize in daylighting design for new construction, but many daylighting techniques can be used in existing homes, as well. Even homes in regions with predominantly overcast days can benefit, as daylight on such days still offers adequate illumination and, often, more-diffuse and even light than brilliantly sunny days.

Along with the solar-heating movement, a less known but highly regarded design science has stepped to the fore—“daylighting,” the use of natural light to illuminate the interiors of structures. Of course, this concept is as old as the window itself, but relatively recent advances in lighting research, window and glazing technology, and lighting controls have opened up new horizons for daylighting.

Homeowners love the qualities of natural light, as evidenced by the billions of dollars spent each year on remodeling, often in an effort to achieve more interior light and a greater sense of space. But while homeowners can enjoy and benefit from more natural light by taking advantage of selective daylighting principles and materials, comprehensive daylighting systems don’t make sense for most homes.

For one thing, the potential energy savings are not the same as for commercial and institutional buildings. Though houses do use plenty of electricity for lighting, high-wattage electrical appliances and heating are what gobble up the lion’s share of a home’s power usage. In addition, unlike an office or library, many homes are relatively unoccupied during daylight hours, which shifts a larger percentage of electrical usage to the evenings.

The need for control is different, too. At home, it’s easy to flip off the lights when they’re not needed. Sophisticated controls that automatically raise and lower indoor artificial light levels according to daylight are not necessary.

Providing natural light in houses is often fundamental to their design. As Russell Leslie and Kathryn Conway point out in “The Lighting Pattern Book for Homes,” published by Rensselaer’s Lighting Research Center, “Homes often have generous amounts of daylight, and residential building codes require that most rooms have windows. Typical residential rooms are small enough so that daylight can reach deep into the room, particularly if windows are located high on the wall.”

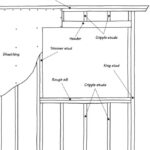

Adding windows for more light is a somewhat obvious solution, although this could be pricy. Clerestory windows, located on the upper part of a wall, can bounce natural light off the ceiling, increasing illumination. Skylights are another good option, particularly in halls or other enclosed spaces that have few, if any, windows.

Discuss with a professional window contractor whether the costs of new window installation justify the potential energy savings. And be aware that too much sunlight can cause glare, making people close blinds and turn on lights—exactly the opposite of the goal they were trying to achieve.

To direct light coming through windows, use louvers or operable blinds. Another option is to install a “light shelf”—a horizontal, light-colored or metal shelf set across a window to ricochet light off the ceiling and back into the room. This shelf is normally located about 12 inches from the top of the window for a standard 8-foot ceiling.

Using light-colored paint is another way to enhance the reflection of natural light in a room. Where appropriate, you can select paint with a high reflective value.

The bottom line is this: If you’d like to get more natural light into your home, consider some of the basic daylighting materials and techniques available.

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has:

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has: