This helpful how-to article explains the best way to drill a hole. It explains electric drills, drill bits, the concept of counterboring, and more.

Drilling holes is a necessary task in many different types of repairs and improvements. You need to drill holes for screws, bolts, dowels, locksets, hinges, masonry fasteners, wires, pipes, and more. Electric drills are used for driving screws and other jobs.

An electric drill is classified by the biggest bit shank that can be accommodated in its chuck (jaws), most commonly 1/4-inch, 3/8-inch, or 1/2-inch. The bigger the chuck size, the higher the power output, or torque.

Electric drills are rated light, medium, and heavy-duty. A heavy-duty model is only needed if you’ll be using it daily or for long, uninterrupted sessions. In addition to single- speed drills, there are variable-speed models that allow you to use the appropriate speed for the job-very handy when starting holes, drilling metals, or driving screws. Reversible gears are good for removing screws and stuck bits.

For most jobs, the 3/8-inch variable-speed drill is your best bet as it can handle a wide range of bits and accessories. Tool catalogs and hardware stores are brimming with special drill bits, guides, and accessories for electric drills. If you’re drilling large holes in masonry, you’ll need a 1/2-inch drill or a hammer drill; both can be rented.

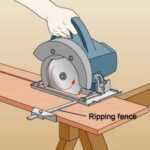

When operating an electric drill, clamp down the materials whenever possible, particularly when using a 3/8- or 1/2-inch drill. Wear safety goggles, especially when drilling masonry or metal. If your drill allows, match the speed to the job, using the highest speeds for small bits or soft woods, and slower speeds for large bits when drilling hard woods or metals.

Don’t apply much pressure when you’re drilling, and don’t turn off the motor until you’ve removed the bit from the material.

When drilling tough metal, lubricate it with cutting oil as you go. If you want to stop at a certain depth, buy a stop collar designed for the purpose, use a pilot bit, or wrap tape around the bit at the correct depth to serve as a visual guide.

If you’re boring large holes in hard woods or metal-especially with oversize twist bits-or driving ordinary screws into all but the softest of woods, first make a smaller pilot hole. Back the bit out occasionally to cool it and clear out the waste.

A pilot hole needs to be sized properly so that it allows the screw to enter the wood without too much resistance but is small enough to give the screw’s threads solid material to grab and hold onto.

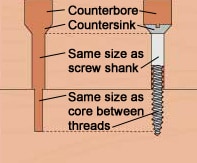

To counterbore for a flat-head screw, you will need to drill three separate holes, as shown in the illustration, unless you utilize a special “pilot bit” that drills all three holes-for the counterbore, shank, and threads-all at once.

What Is a Counterbore?

No, a counterbore is not a tedious bartender. Although the term “counterbore” is sometimes used as a noun, it is more commonly a verb that describes increasing a hole’s diameter by drilling a larger-diameter hole at one end to make room for the head of a screw or bolt.

In some cases, a counterbored hole is filled with a decorative wood plug to conceal the fastener’s head. To countersink a hole is slightly different: This means to drill a shallow hole that will allow a screw’s head to sit flush with the surface.

To counterbore a hole, it’s easiest to drill the larger-diameter hole first, then drill the deeper hole for the fastener’s shaft. You should use a spade bit-or, better-a Forstner bit, which will create a flat-bottomed hole.

It’s hard to say where the term counterbore came from. In early 17th century France, counter-or contre-was a fencing term, used to describe a circular parry around the tip of a competitor’s sword.

All uses of the word “counter” seem to have the same reference to opposition, except one: the counter used in a shop (perhaps this type of hole was first used in a bench top).

“Bore,” a word that both describes a hole and the process of making one, dates back to the early 11th century with roots in many languages, referring to auguring a hole as for a gimlet.

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has:

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has: