Thermostats measure your home’s ambient temperature and use that information to activate your furnace or air conditioner, depending on the thermostat’s setting.

The first thermostat was invented in the early 17th century by a Dutch man, Cornelis Drebbel, who placed a float inside a mercury thermometer and connected that apparatus to a damper cover on a furnace. When the mercury climbed to a certain level, the float caused the damper to close.

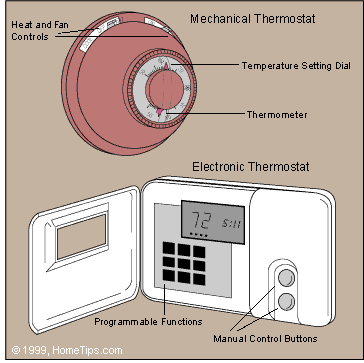

Today’s thermostats do fundamentally the same thing, but the technology has come a long, long way since then. Essentially a heat-activated switch, a thermostat has a temperature sensor that causes the switch to open or close, completing or interrupting an electrical circuit that runs the house’s heating or cooling system. It can do this job either mechanically or via electronic circuitry.

A state-of-the-art thermostat, probably best exemplified by the Nest Learning Thermostat, learns a family’s behaviors and preferences, digests this information, and controls the temperature accordingly—essentially programming itself. When connected to a home’s Wi-Fi, it can be managed remotely from a smartphone, tablet, or laptop computer. For more about this, see Thermostats Buying Guide.

Programmable Electronic Thermostats

Electronic thermostats utilize an electronic heat-sensing element and circuitry to sense temperature changes and turn on heating or cooling equipment. Like a small computer, they are programmable; their timers allow you to warm up your house before you get out of bed in the morning and before you come home from work and be set at different temperatures for different times of the day. This means you can closely align room temperatures with your needs, ensuring comfort without wasting energy. Top of the line “learning” thermostats such as the Nest Thermostat mentioned above are sophisticated versions of the electronic thermostat.

Electromechanical Thermostats

Electromechanical thermostats have some type of mechanical temperature sensing device—typically a bi-metal coil or strip. As the name suggests, this type is made from two connected metals. Changes in temperature cause these metals to expand and contract at different rates, causing the coil or strip to move.

The bi-metal coil or strip is connected to a device that completes an electrical circuit. In the case of Honeywell’s electromechanical thermostats, a spiral bi-metal sensor attaches to a small glass vial that contains mercury; the coil’s movement causes the vial to tilt one way or the other.

Because one of the properties of mercury is that it conducts electricity, the circuit is completed when the mercury flows to one end of the vial where there are two separated electrical contacts.

A thermostat that operates both heating and cooling units has two contacts at each end of the vial. When the vial tilts in one direction, the mercury flows to that end and completes a circuit that calls for heat. When the system is switched to the cooling cycle, the mercury flows to the other end of the vial to turn on the cooling.

Disposal of the small amount of mercury from this type of thermostat has become an issue in recent years. Pilot programs are being tested in some states for recycling old mercury-containing thermostats; Honeywell has been a very active player in these initiatives.

Some electromechanical thermostats, such as those made by GE, work similarly but complete the circuit with a magnetic snap reed switch.

Zoned Heating & Cooling

Sophisticated zone-controlled home climate systems divide the house into several separate areas that may each be controlled by separate settings and times on individual thermostats. With zone controls, thermostats open and close dampers, sending warm or cool air when and where needed.

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has:

Don Vandervort writes or edits every article at HomeTips. Don has: